Survival Analysis

Overview

Class Date: 9/25/2025 -- In Class

Teaching: 90 min

Exercises: 30 minQuestions

How is time-to-event data structured?

What are the elements that separate time-to-event data from single-point observations?

How do we visualize time-to-event data?

What statistical tests are available for time-to-event data hypothesis testing?

Objectives

Describe the basic structure of time-to-event data.

Understand censoring and how it affects time-to-event data.

Use the

survivalpackage to generate survival curves and age-specific mortality plots.Use the Log-Rank tests to evaluate statistical differences between time-to-event observations between groups.

In Class

So far we have mostly been dealing with data that meets that basic assumptions of a t-test or other common statistical tests. In this class, we are going to look at a category of data that requires special consideration. Time-to-event data (e.g. survival or lifespan data) violates several assumptions made by many of our standard tests:

- It is not generally normally distributed.

- Observations are not independent (more below on this).

- Data is often censored.

In the following sections we will examine common methods for formatting, displaying, and analyzing time-to-event data, and how to implement these methods in R.

Missing data and censoring

When you are dealing with time-to-event data, subjects are selected (aka sampled) and observed repeatedly until some event occurs (or does not occur). This opens the possibility that a study will be completed without an observation of the event under study actually occurring. This can happen for a few reasons:

- A subject is removed from the study (e.g. a patient in a drug trial stops taking the drug on their own)

- A related event occurs that precludes occurrence of the event of interest (e.g. a patient in a cancer drug trial is killed in a car accident; this prevents the event of interest, “death from cancer” from occurring)

- A subject remains in the study, but the study concludes before the event of interest occurs

To deal with these cases, we include the subject in the study but use censoring to indicate that the event of interest was not observed between specific defined time points. There are three types of censoring:

- Right-censoring: the event of interest occurs after some time t, but the specific time of is unknown.

- e.g. a subject dies of an unrelated cause

- e.g. a subject is still alive at the end of the study

- e.g. a subject leaves the study prior to its conclusion

- Left-censoring: an individual’s entry date is unknown (e.g. birthdate in lifespan studies).

- e.g. a subject infected with a pathogen enters a study, but the infection date is unknown

- Interval-censoring: the event of interest occurred in a known interval, but the precise time is unknown.

- e.g. a patient is diagnosed with the disease of interest during a follow-up visit after a study concludes

Right-censoring is the most common. This is particularly true when using a model organism in the lab, where the birthdate or other entry criteria can be tightly controlled, but an individual exiting a study can happen for various reasons. We will only examine right-censoring in this class, but be aware of the other forms, particularly if you are dealing with data collected from human subjects.

Why not just exclude censored data?

One option for dealing with an unexpected event (e.g. your mouse escapes 18 months into your lifespan study) is to just leave out the data for that individual. This has at least two problems for your analysis:

- Bias: What if the unexpected event is correlated with you outcome of interest? For example, perhaps only mice that are still healthy and likely to have a long remaining lifespan will be capable of escaping at 18 months of age. By not considering these mice, you will shift the distribution of measured lifespan values toward shorter lifespan.

- Power: Because the procedure in these studies is to (1) select a sample, and (2) make repeated observations until the event occurs, we already have observations collected up until the time point when an individual is censored. Removing the individual from the analysis removes potentially valuable data (e.g. we know that the mouse lived at least 18 months). Including these individuals with proper censoring will increase your statistical power to detect changes.

Survival curves

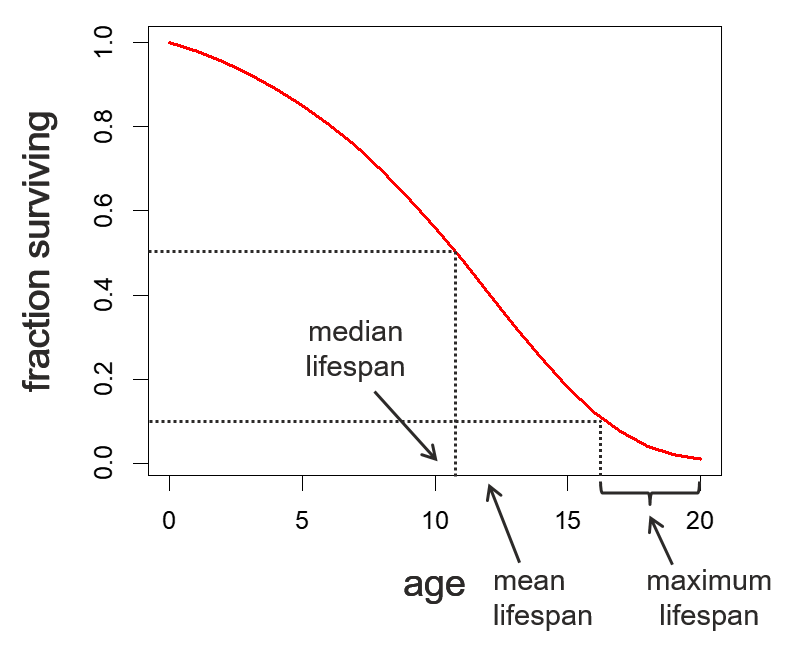

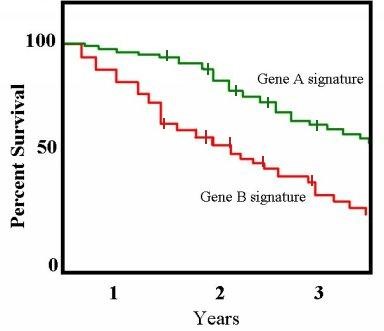

The most common form of data presented for time-to-event data is the survival curve. The curve shows the fraction or percentage of the population surviving at a given time. The time measure can be age (as is the case for lifespan) or some other relevant defined point (e.g. diagnosis with a disease, cancer remission, time of treatment).

Of course, we generally don’t know the survival for every individual in the population and need to draw a best estimate from our sample data. To deal with this issue, we use two tools called the Life Table, to generate information about the survival characteristics over time, and Kaplan-Meier curves to draw approximate survival curves from sample data.

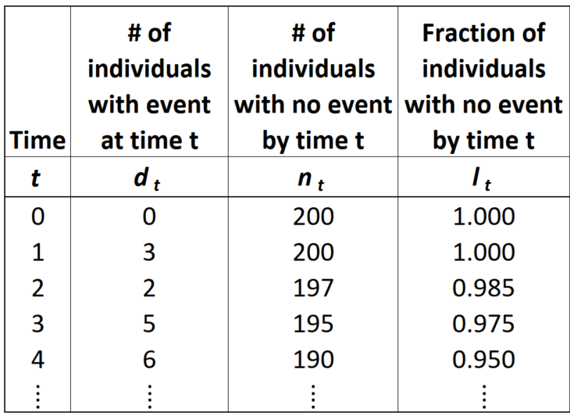

The life table

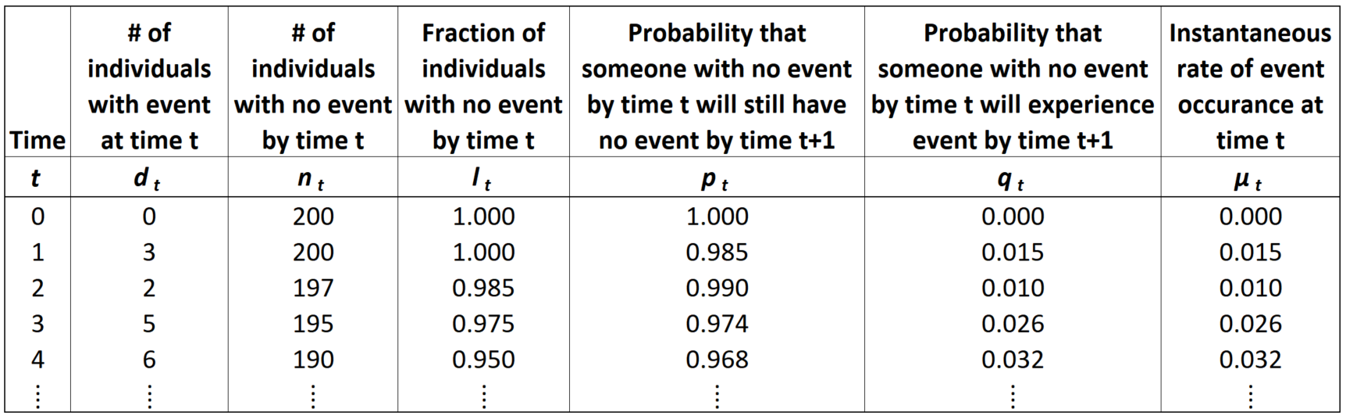

The Life Table is a systematic way to tabulate observations and estimate survival parameters based on sample data. A Life Table has the following basic information:

- \(t_0 =\) start time, relative to the time period of interest (e.g. for lifespan data, each individual’s birth is set to time 0, even if they were born on different dates)

- \(t =\) observation time

- \(d_t =\) number of events observed at time t

- \(n_0 = \sum d_t =\) original sample size (number of individuals in the sample prior to censoring or events)

- \(n_t = n_0 - \sum_{x = 0}^{t-1} d_x =\) number of individuals at risk at time t (e.g. sampled, uncensored individuals with no event by time t)

- \(l_t = \frac{n_t}{n_0} =\) fraction of the sample remaining at risk by time t

- \(S(t) \approx l_t =\) survival function, the fraction of the population at risk at (aka “surviving to”) time t

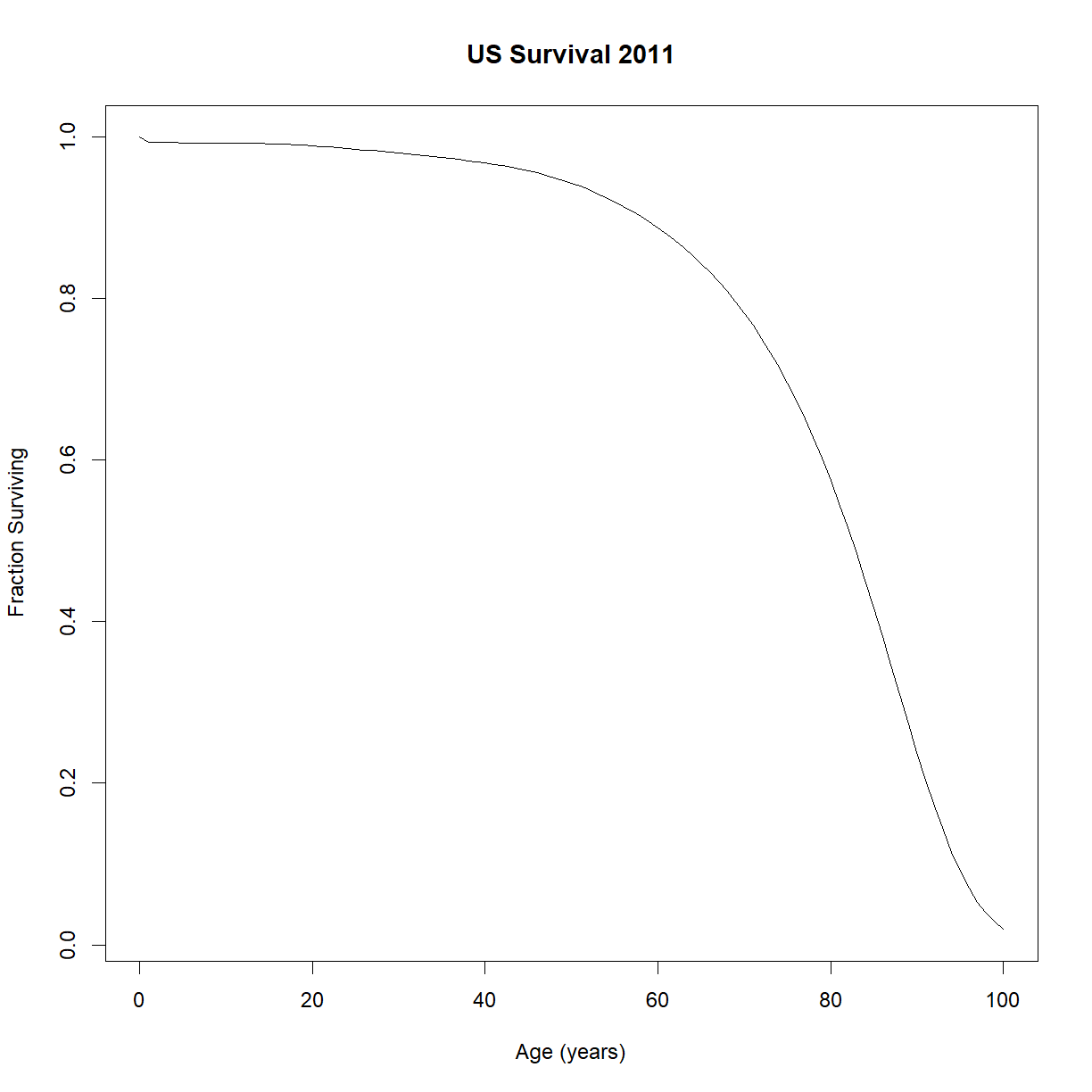

We estimate the survival function by plotting \(l_t\) vs. age \(t\). Let’s examine the survival of the US population as an example. The life table is stored in US2011.life.table.txt.

lt <- read.delim("./data/US2011.life.table.txt")

str(lt)

'data.frame': 101 obs. of 7 variables:

$ age: int 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 ...

$ qx : num 0.006058 0.000415 0.000264 0.000208 0.000167 ...

$ lx : int 100000 99394 99353 99327 99306 99289 99274 99261 99249 99239 ...

$ dx : chr "606" "41" "26" "21" ...

$ Lx : int 99470 99374 99340 99316 99298 99282 99268 99255 99244 99234 ...

$ Tx : int 7870915 7771445 7672071 7572731 7473415 7374117 7274835 7175567 7076312 6977068 ...

$ ex : num 78.7 78.2 77.2 76.2 75.3 74.3 73.3 72.3 71.3 70.3 ...

Note that what I called \(n_t\) this particular data set calls \(l_x\) (and that all subscripts are “x” instead of “t”). Some of the above variables (e.g. our \(l_t\)) are missing. To start, let’s rename the variables to match our convention and calculate \(l_t\):

# rename life table variables

names(lt) <- c("t","qt","nt","dt","Lt","Tt","et")

# calculate l{t}

lt$lt <- lt$nt/max(lt$nt)

head(lt)

t qt nt dt Lt Tt et lt

1 0 0.006058 100000 606 99470 7870915 78.7 1.00000

2 1 0.000415 99394 41 99374 7771445 78.2 0.99394

3 2 0.000264 99353 26 99340 7672071 77.2 0.99353

4 3 0.000208 99327 21 99316 7572731 76.2 0.99327

5 4 0.000167 99306 17 99298 7473415 75.3 0.99306

6 5 0.000151 99289 15 99282 7374117 74.3 0.99289

Now we can plot the survival curve:

plot(lt$t,lt$lt, type = "l",

main="US Survival 2011",

xlab="Age (years)",ylab="Fraction Surviving")

Great! That looks like a standard survival curve to me. We can see that median lifespan is around 85 years and maximum is out around 100. The tip of the tail (which won’t appear on this chart since we only has ~100,000 people out of ~300,000,000) is really out at 122 or so.

From the equation for \(l_t\), we can see that it depends on \(n_t\), which in turn depends on all of the previously observed events (\(d_0\) to \(d_t-1\)). Thus the survival function cannot be considered an variable with independent observations. This is one reason we can’t use a t-test to make comparisons. For that we need to look at a different aspect of time-to-event data. A complete life table will have a few more columns:

- \(p_t = l_{t+1}/l_t =\) probability that someone with no event at time t will still have no event by time t + 1.

- \(q_t = 1 - p_t =\) probability that someone with no event at time t will experience the event by time t + 1.

- \(\lambda(t) = -\frac{\delta}{dx} ln[S(x)] \approx -ln(p_t) =\) instantaneous rate at which the event occurs at time t; the slope of the log of the survival function. For survival data specifically, this is also called \(\mu_x =\) age-specific mortality.

The last variable, \(\lambda(t)\) is called the hazard function (aka hazard rate, \(h(x)\)), or in the context of survival data, age-specific mortality or force of mortality (\(\mu_x\)). Conceptually, age-specific mortality represents the chance of an individual dying at that specific age.

\(\lambda(t)\), while not normally distributed, does not depend on previous observations, and can thus be considered a variable for which observations are independent. This allows us to make statistical comparisons. Let’s look at how \(\lambda(t)\) behaves.

# calculate pt and lambdat

lt$pt <- 1 - lt$qt

lt$lambdat <- -log(lt$pt)

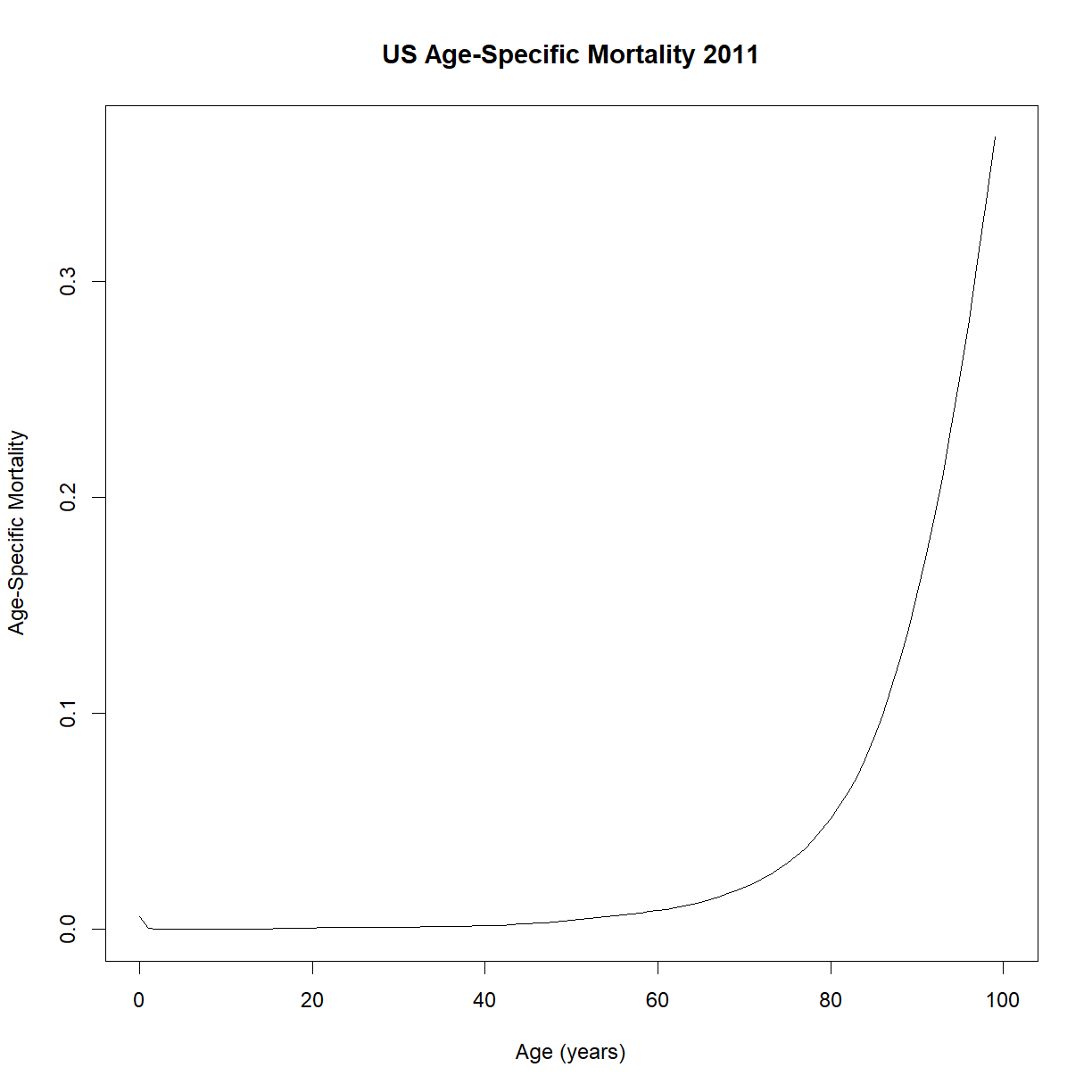

# plot age specific mortality -- does the shape look familiar?

plot(lt$t, lt$lambdat, type = "l",

main="US Age-Specific Mortality 2011",

xlab="Age (years)", ylab="Age-Specific Mortality")

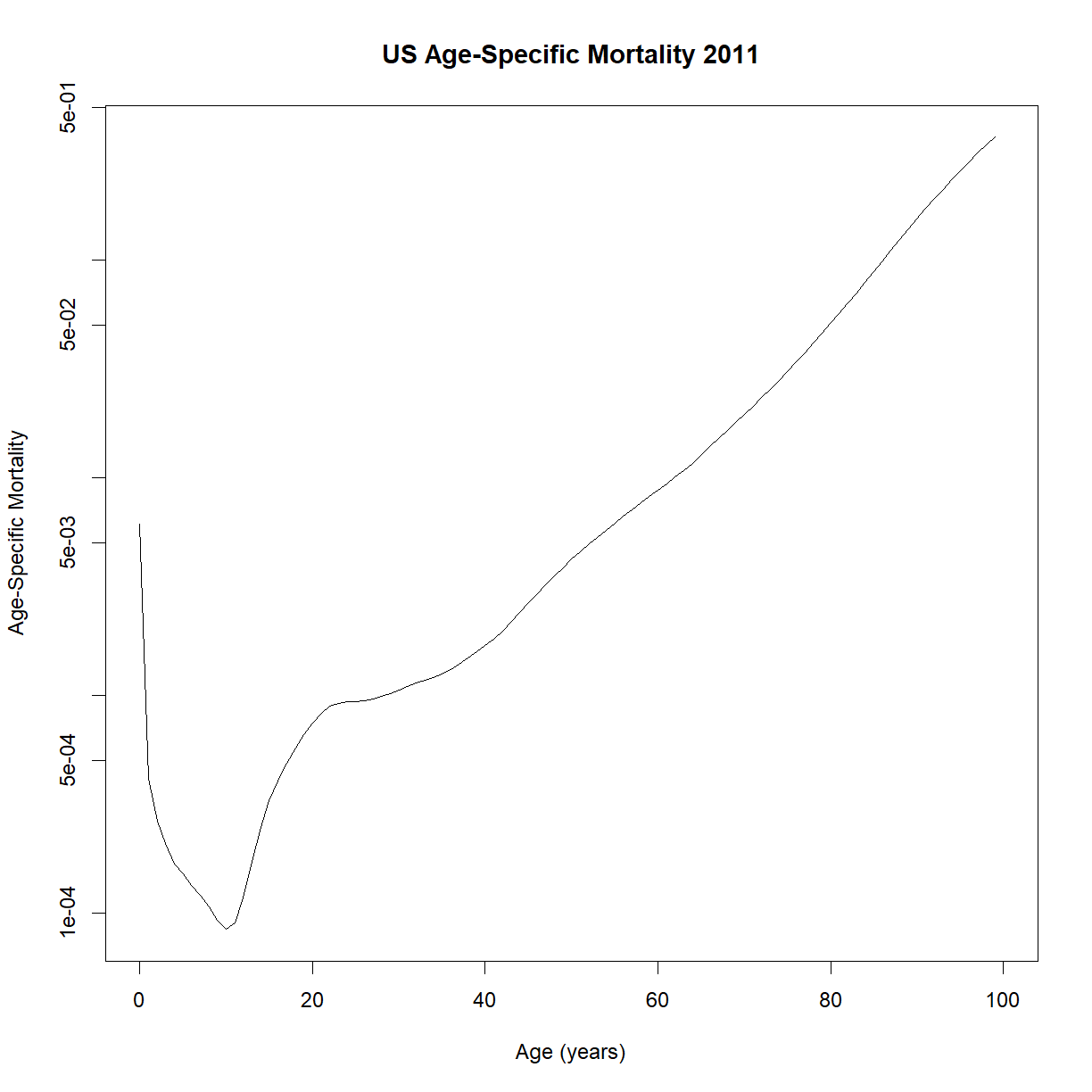

Does that shape look familiar? It appears to increase exponentially with age. Try plotting the y-axis on a log-scale (using the log = "y" argument in plot; alternatively, you could plot log(lt$lambdat) on the y-axis):

plot(lt$t, lt$lambdat, type = "l", log="y",

main="US Age-Specific Mortality 2011",

xlab="Age (years)",

ylab="Age-Specific Mortality")

Despite the some odd behavior during the early part of life, age-specific mortality appears to increase linearly during the majority of adulthood. That looks like something we can model!

Minimum age-specific mortality

As an aside, what is up with that minimum point? At what age does that occur?

lt$t[which.min(lt$lambdat)][1] 10

What happens to humans at roughly 10 years of age? Puberty! Thinking from an evolutionary perspective, it makes sense that the minimum change of dying should occur at the point of maximum reproductive potential. Ability to reproduce is a primary driver of species survival, and remaining reproductive potential only decreases with increasing age.

Incidentally, this is one of the major categories of theory for why we age in the first place. It isn’t so much that aging is selected for, but that the decline in “remaining reproductive potential” decreases as we get older, and thus the selection pressure steadily reduces. If an allele gives us a boost to reproduction or health early in life, it may be selected for even if it causes a fatal disease later in life.

Kaplan-Meier curves

We never actually know the “real” shape of the survival curve for our population, or even our sample, because of the structure of time-to-event data. This is true for two reasons:

- We often have missing data that requires censoring (i.e. the event was never observed)

- Subjects are only observed at discrete time points, so we don’t have access to the exact time that the event occurred. We instead know that the event had not occurred at some time t - 1, but that the event had occurred by time t.

There is a type of survival curve estimator called the Kaplan-Meier curve which allows us to approximate the shape of the survival curve for a given set of time-to-event observations. Kaplan-Meier curves have the following properties.

- Estimates true survival curve when data is missing (i.e. when one or more observations is censored)

- Assumes that no deaths occur between observation times (i.e. approximates that each event occurred at the observation time, rather than at some unknown time between observations)

- Tick marks are used to indicate time at which a subject was censored for missing data.

- For the purposes of drawing the curve, censored individuals are included in the “total” or “at risk” sample size up until the time point where they were censored. After that point, the change in curve height for a new event occurrence is dependent on the reduced sample size with out the censored individual.

This is because the pool of patients remaining “at risk” for the event drops when either an event is experienced or when a patient is censored.

When an event occurs, the curve drops by a fraction of the remaining “at risk” pool at that time point. As patients are censored without an observed event, the remaining “at risk” pool decreases. Thus subsequent events drop the remaining % remaining by a larger and larger margin. A good step-by-step guide to how Kaplan-Meier curves are drawn can be found here.

Let’s look at our data from the inbred mouse aging study for an example. Make sure that the survival package is loaded, and read in the mouse lifespan data. For our purposes, let’s look specifically at the strain BUB/BnJ, which has a number of censored mice.

# load survival package

library("survival")

# read in inbred strain lifespan data

data.surv <- read.delim("data/inbred.lifespan.txt")

# grab the subset of data for BUB/BnJ

surv.bub <- data.surv[data.surv$strain == "BUB/BnJ",]

# check out the data

str(surv.bub)

'data.frame': 64 obs. of 5 variables:

$ strain : chr "BUB/BnJ" "BUB/BnJ" "BUB/BnJ" "BUB/BnJ" ...

$ sex : chr "f" "f" "f" "f" ...

$ animal_id : chr "174" "175" "176" "177" ...

$ lifespan_days: int 328 343 266 357 523 670 279 635 216 538 ...

$ censor : int 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 ...

For survival analysis, the survival packages uses an odd notation for simulating the survival curve. In order to include data censoring, instead of using lifespan_days directly as the dependent variable, we use the notation Surv(time, event status). This tells R that we have a set of censored survival data with observed event times (lifespan_days), and some mice that were censored and not observed to have died (censor). Let’s contrast the data format here to the life table that we looked at above:

- Life tables describe populations, providing information about the number or fraction of individuals in different categories, or other population-level information like age-specific mortality for individuals within that population.

- Mortality data like that provided in the inbred mouse aging dataset describes individuals, providing phenotype data for each individual.

A note on the lifespan variable. We have emphasized that the sampling method for survival data involves repeated binary observations (the event did/did not occur) at subsequent time points, but the mortality data simply provides a single data point for lifespan_days. The underlying assumption is that the individual was observed at all previous time points, but that the event of interest occurred at the reported time. If an individual was not censored (censor = 0), then we know the event occurred at that time point. If the individual was censored (censor = 1), then we know that the mouse was last observed alive at the reported time point.

In our case, we use the lifespan_days as the time that we observed the event, and censor as our status variable. An important note: what Surv() wants for status is whether the event occurred. In this particular data set, the event was assumed to occur unless something odd happened (e.g. the mouse escaped), so censor is “0” when the mouse died (the event occurred) and “1” when something else happened (e.g. the mouse was “censored” and removed from the study because death, the event, was never observed). Thus we need to tell R that censor == 0 means “the event occurred”.

The survfit() function builds the life table that we need for our analyses. We embed the Surv() object as the dependent variable in side the survfit() function. survfit() always needs an independent variable. If you want to just plot all of the data as a single curve, you can just give it “1”, which tells R not to subset the data before running the analysis:

# calculate life table for BUB/BnJ mice

survfit.bub <- survfit(Surv(lifespan_days, censor == 0) ~ 1, data = surv.bub)

# use summary() to look at the life table

summary(survfit.bub)

Call: survfit(formula = Surv(lifespan_days, censor == 0) ~ 1, data = surv.bub)

time n.risk n.event survival std.err lower 95% CI upper 95% CI

260 52 1 0.9808 0.0190 0.94414 1.000

266 51 1 0.9615 0.0267 0.91066 1.000

279 47 1 0.9411 0.0330 0.87852 1.000

287 46 1 0.9206 0.0381 0.84885 0.998

301 45 1 0.9002 0.0424 0.82076 0.987

307 44 1 0.8797 0.0461 0.79380 0.975

328 43 1 0.8592 0.0494 0.76772 0.962

341 42 1 0.8388 0.0523 0.74236 0.948

343 41 1 0.8183 0.0549 0.71759 0.933

354 40 2 0.7774 0.0592 0.66954 0.903

357 38 1 0.7570 0.0611 0.64616 0.887

366 37 1 0.7365 0.0628 0.62315 0.870

383 35 1 0.7155 0.0644 0.59969 0.854

426 34 1 0.6944 0.0659 0.57658 0.836

447 33 1 0.6734 0.0672 0.55380 0.819

455 32 1 0.6523 0.0683 0.53133 0.801

457 31 1 0.6313 0.0692 0.50916 0.783

493 30 1 0.6102 0.0701 0.48727 0.764

495 29 1 0.5892 0.0707 0.46566 0.746

523 28 1 0.5682 0.0713 0.44431 0.727

538 27 1 0.5471 0.0717 0.42322 0.707

551 26 1 0.5261 0.0719 0.40239 0.688

608 25 1 0.5050 0.0721 0.38180 0.668

621 24 1 0.4840 0.0721 0.36147 0.648

628 23 1 0.4629 0.0719 0.34138 0.628

635 22 1 0.4419 0.0717 0.32154 0.607

670 21 1 0.4209 0.0713 0.30195 0.587

678 20 1 0.3998 0.0708 0.28261 0.566

693 19 2 0.3577 0.0693 0.24472 0.523

722 17 1 0.3367 0.0683 0.22618 0.501

726 16 1 0.3156 0.0672 0.20792 0.479

768 15 1 0.2946 0.0660 0.18996 0.457

810 14 1 0.2736 0.0645 0.17230 0.434

818 13 1 0.2525 0.0629 0.15498 0.411

855 12 1 0.2315 0.0611 0.13801 0.388

867 11 1 0.2104 0.0590 0.12143 0.365

873 10 1 0.1894 0.0568 0.10526 0.341

874 9 1 0.1683 0.0542 0.08955 0.316

875 8 1 0.1473 0.0514 0.07438 0.292

888 7 1 0.1263 0.0481 0.05980 0.267

889 6 2 0.0842 0.0403 0.03297 0.215

904 4 1 0.0631 0.0353 0.02112 0.189

965 3 1 0.0421 0.0291 0.01084 0.163

1020 2 1 0.0210 0.0208 0.00303 0.146

1034 1 1 0.0000 NaN NA NA

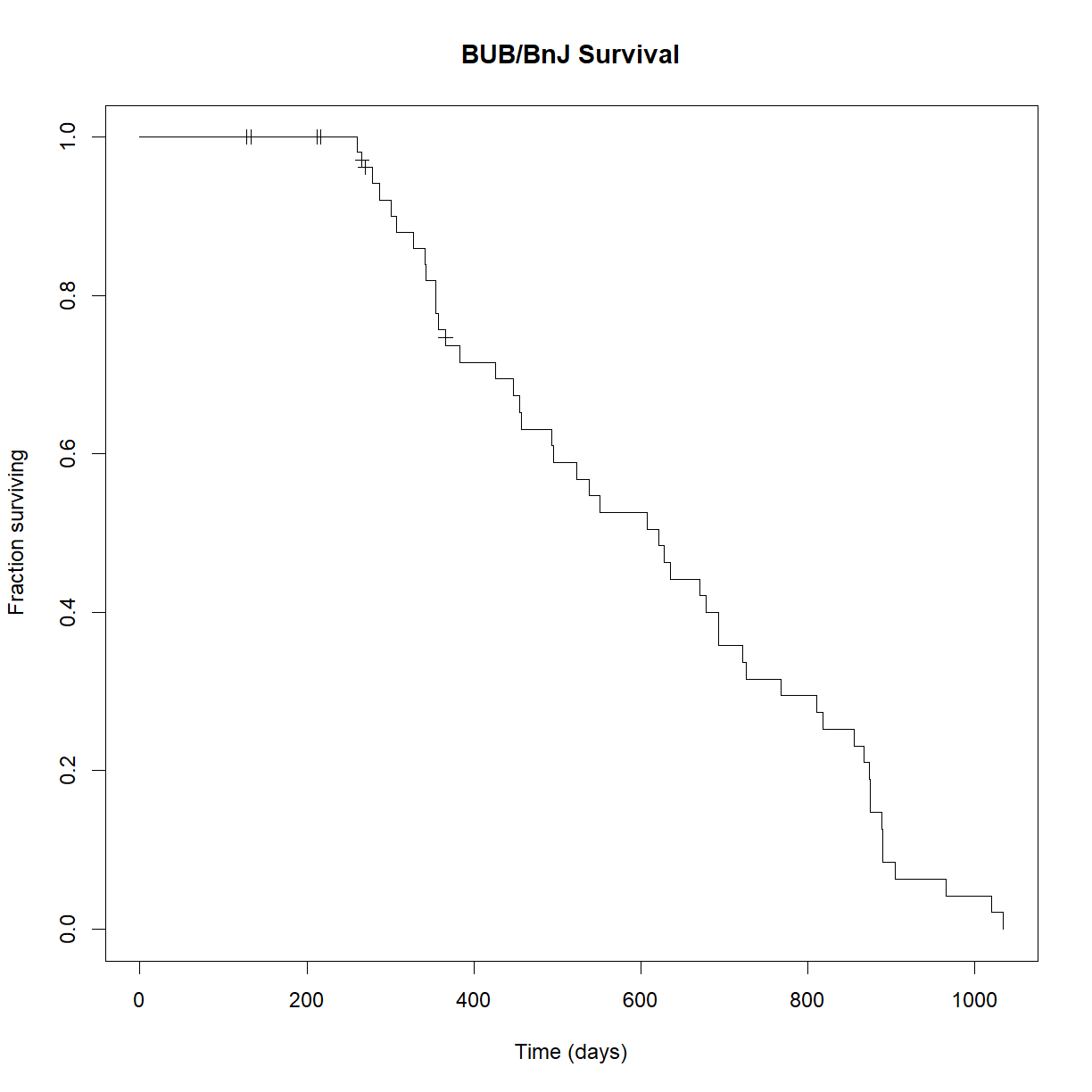

Now that we have the survival function, the plot() function already knows what we want to do with it: plot the Kaplan-Meier curve:

# Plot the Kaplan-Meier curve

plot(survfit.bub, xlab = "Time (days)",

ylab="Fraction surviving",

conf.int=FALSE, # turn of confidence intervals

mark.time = TRUE, # mark time of censor

main="BUB/BnJ Survival")

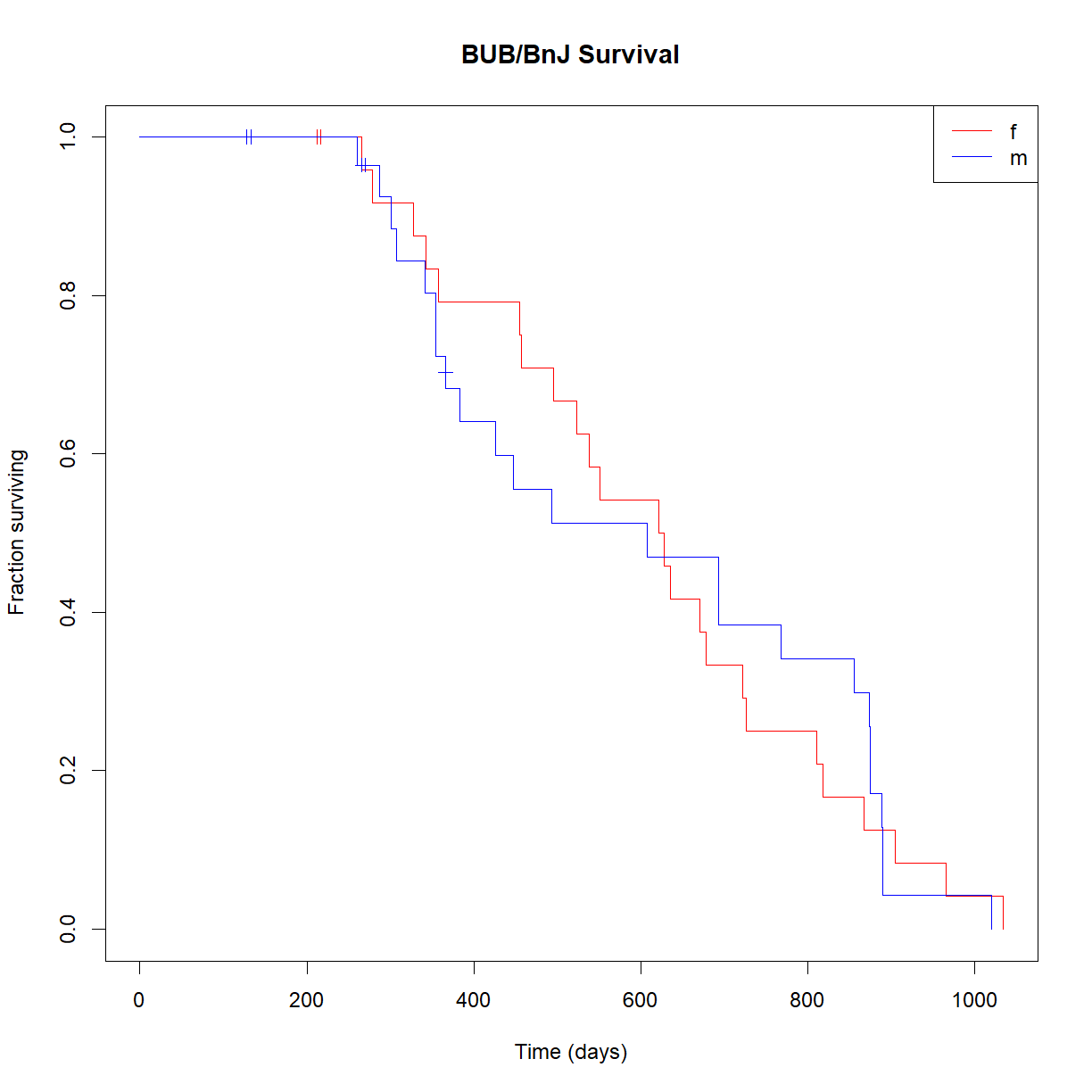

We can also break the data down into the two sexes. We do this using the dependent variable at the survfit() step:

# calculate life table for BUB/BnJ mice with sex as an independent variable

survfit.bub.sex <- survfit(Surv(lifespan_days, censor == 0) ~ sex, data = surv.bub)

# use summary() to look at the life table

summary(survfit.bub.sex)

Call: survfit(formula = Surv(lifespan_days, censor == 0) ~ sex, data = surv.bub)

sex=f

time n.risk n.event survival std.err lower 95% CI upper 95% CI

266 24 1 0.9583 0.0408 0.88163 1.000

279 23 1 0.9167 0.0564 0.81250 1.000

328 22 1 0.8750 0.0675 0.75221 1.000

343 21 1 0.8333 0.0761 0.69681 0.997

357 20 1 0.7917 0.0829 0.64478 0.972

455 19 1 0.7500 0.0884 0.59531 0.945

457 18 1 0.7083 0.0928 0.54795 0.916

495 17 1 0.6667 0.0962 0.50240 0.885

523 16 1 0.6250 0.0988 0.45845 0.852

538 15 1 0.5833 0.1006 0.41598 0.818

551 14 1 0.5417 0.1017 0.37489 0.783

621 13 1 0.5000 0.1021 0.33513 0.746

628 12 1 0.4583 0.1017 0.29668 0.708

635 11 1 0.4167 0.1006 0.25954 0.669

670 10 1 0.3750 0.0988 0.22373 0.629

678 9 1 0.3333 0.0962 0.18930 0.587

722 8 1 0.2917 0.0928 0.15636 0.544

726 7 1 0.2500 0.0884 0.12502 0.500

810 6 1 0.2083 0.0829 0.09551 0.454

818 5 1 0.1667 0.0761 0.06813 0.408

867 4 1 0.1250 0.0675 0.04337 0.360

904 3 1 0.0833 0.0564 0.02211 0.314

965 2 1 0.0417 0.0408 0.00612 0.284

1034 1 1 0.0000 NaN NA NA

sex=m

time n.risk n.event survival std.err lower 95% CI upper 95% CI

260 28 1 0.9643 0.0351 0.89794 1.000

287 24 1 0.9241 0.0517 0.82807 1.000

301 23 1 0.8839 0.0632 0.76836 1.000

307 22 1 0.8438 0.0720 0.71386 0.997

341 21 1 0.8036 0.0790 0.66280 0.974

354 20 2 0.7232 0.0892 0.56792 0.921

366 18 1 0.6830 0.0929 0.52328 0.892

383 16 1 0.6403 0.0964 0.47678 0.860

426 15 1 0.5977 0.0989 0.43205 0.827

447 14 1 0.5550 0.1007 0.38893 0.792

493 13 1 0.5123 0.1016 0.34732 0.756

608 12 1 0.4696 0.1017 0.30718 0.718

693 11 2 0.3842 0.0995 0.23125 0.638

768 9 1 0.3415 0.0972 0.19552 0.597

855 8 1 0.2988 0.0939 0.16137 0.553

873 7 1 0.2561 0.0897 0.12894 0.509

874 6 1 0.2134 0.0843 0.09843 0.463

875 5 1 0.1708 0.0775 0.07016 0.416

888 4 1 0.1281 0.0689 0.04463 0.368

889 3 2 0.0427 0.0417 0.00628 0.290

1020 1 1 0.0000 NaN NA NA

Note that survfit() builds separate life tables for male and female mice. Now we can use plot() to generate the Kaplan-Meier curves for our new survfit object:

# Plot the Kaplan-Meier curve

plot(survfit.bub.sex, xlab = "Time (days)",

ylab = "Fraction surviving",

col = c("red","blue"),

conf.int=FALSE, # turn of confidence intervals

mark.time = TRUE, # mark time of censor

main = "BUB/BnJ Survival")

# add legend

legend("topright", lty = 1,

col = c("red","blue"),

legend = c("f","m"))

The log-rank test

Now that we can visualize our lifespan data, how do we conduct a hypothesis test to compare different groups? The most common test for lifespan data is the log-rank test (aka logrank or Mantel-Cox test). The log-rank test makes the assumption that the survival functions (\(S(t)\)) are the same for the two groups under the null hypothesis (essentially, this means that any censoring is correlated with survival). What the test does it:

-

Assume that the survival is equal and that any censoring does not impact the survival function.

-

At each observation point, calculate the difference in the number of observed events between comparison groups.

-

Sum the differences across time points to calculate the test statistics: \(z = \frac{\sum_{j=1}^{J} (O_{1j} - O_{2j})}{\sqrt{\sum_{j=1}^{J} V_j}}\)

-

This test statistic is approximately normally distributed and can be used to calculate the probability that the observed difference represents a sample from the null distribution (or not) at a given \(\alpha\).

In R, the survdiff() function performs a log-rank test using the same dependent and independent variable format as survfit(). Let’s use it to see if there are differences in lifespan between male and female BUB/BnJ mice:

logrank.bub <- survdiff(Surv(lifespan_days, censor == 0) ~ sex, data = surv.bub)

logrank.bub

Call:

survdiff(formula = Surv(lifespan_days, censor == 0) ~ sex, data = surv.bub)

N Observed Expected (O-E)^2/E (O-E)^2/V

sex=f 32 24 24.1 0.000882 0.00189

sex=m 32 24 23.9 0.000893 0.00189

Chisq= 0 on 1 degrees of freedom, p= 1

So there is no difference in lifespan between male and female BUB/BnJ mice. There is a quirk with the survdiff() function in R. How do you extract the P-value? Looking at the survdiff object, there doesn’t seem to be a clear way to extract it directly:

str(logrank.bub)

List of 7

$ n : 'table' int [1:2(1d)] 32 32

..- attr(*, "dimnames")=List of 1

.. ..$ groups: chr [1:2] "sex=f" "sex=m"

$ obs : num [1:2] 24 24

$ exp : num [1:2] 24.1 23.9

$ var : num [1:2, 1:2] 11.3 -11.3 -11.3 11.3

$ chisq : num 0.00189

$ pvalue: num 0.965

$ call : language survdiff(formula = Surv(lifespan_days, censor == 0) ~ sex, data = surv.bub)

- attr(*, "class")= chr "survdiff"

Similar to how a t-test uses the t-distribution (which is a modified normal distribution) to calculate a P-value based on the area under a well-defined portion of the probability density curve, the log-rank test calculates a different statistics, called \(\chi\), and uses another well-defined distribution, the \(\chi^2\) distribution, to calculate P-values.

For an obscure and mathematically dense reason, the creator of the survdiff() function decided not to directly report the P-value in the output of the function. However, he did include the calculated value of \(\chi^2\), and R includes a function that defines the \(\chi^2\) distribution, so we can relatively easily calculate it for ourselves.

# extract the value of the chi-squared statistic from the survdiff object

# we also need the number of comparison groups, which defines the degrees

# of freedom for the test (this is stored in the `n` variable)

chisq.bub <- logrank.bub$chisq

n.bub <- logrank.bub$n

# use the chisq statistic to calculate the P-value; the second argument

# is degrees of freedom (df), calculated from n. By default, and based on

# the way the distribution is used in the function, qchisq() returns the

# reciprocol of the P-value (1 - P). Setting `lower.tail = F` reverses

# this and gives the P-value

P.bub <- pchisq(chisq.bub, length(n.bub) - 1, lower.tail = F)

P.bub

[1] 0.9653378

Incidentally, we can similarly calculate the P-value from a t statistic (reported in the t.test() function) in place of chisq and the pt() function in place of the pchisq() function as above.

Summary of survival package notation in R

Surv(age, event)

- Creates a “survival object” that is basically just a function that indicates the comparison we are interested in making

age= age that the event occurredevent= had the event (e.g. death) occurred at observation (1 = yes, 0 = no)

survfit(Surv(age, event) ~ groups)

- Generates a life table from a survival object, subsetted by

groups- Used for plotting survival curves

groups= variable(s) used to subset for group comparison (e.g. sex, genotype)

survdiff(Surv(age, event) ~ groups))

- Conducts a log-rank test on

Surv(age, event)betweengroups

Exercises

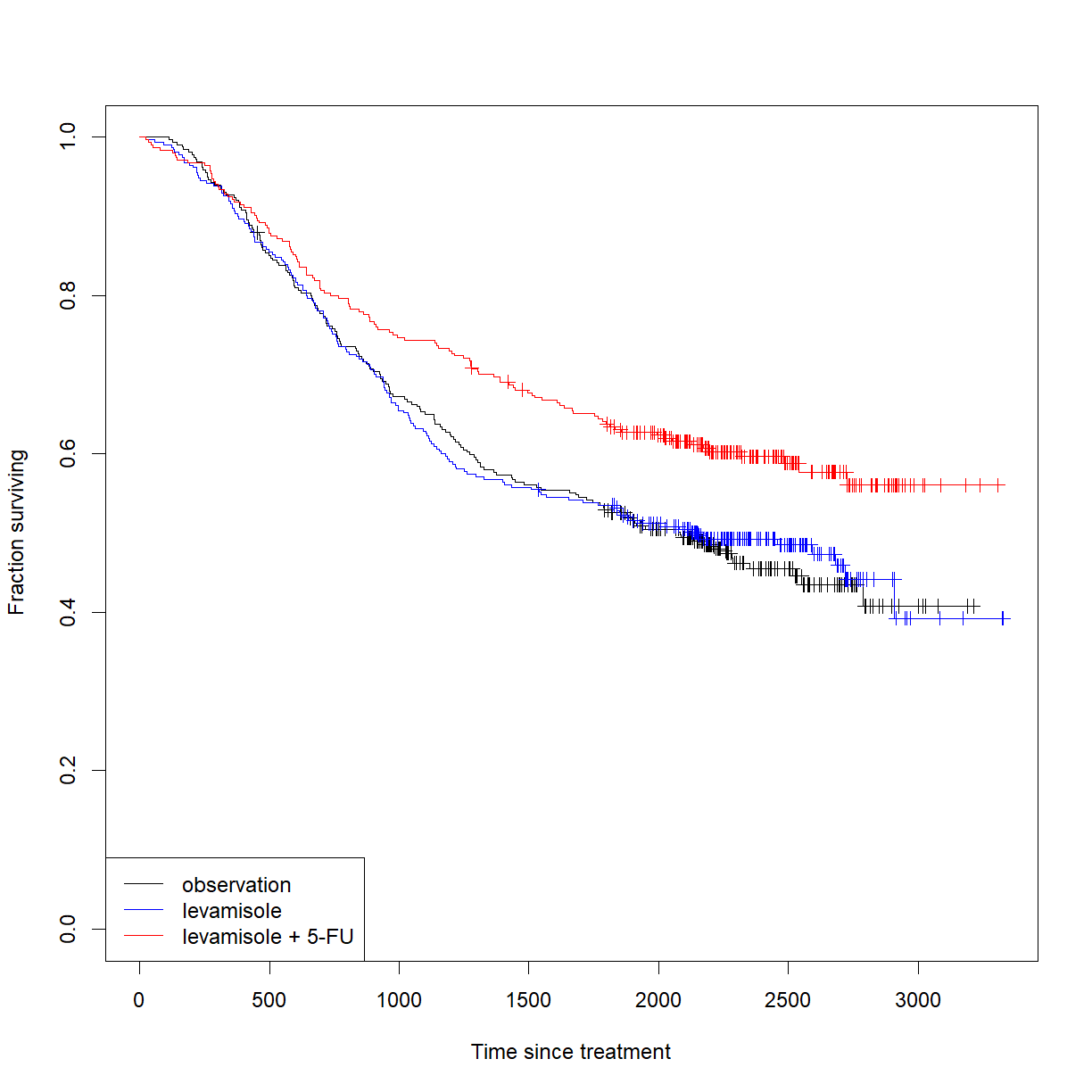

Treating colon cancer with levamisole

The

survivalpackage includes a colon cancer dataset looking at the efficacy of treating patients diagnosed with colon cancer with levamisole as either a monotherapy or in combination with 5-FU. Take a look at thecolondataset:library("survival") # make sure you have the library loaded str(colon)'data.frame': 1858 obs. of 16 variables: $ id : num 1 1 2 2 3 3 4 4 5 5 ... $ study : num 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ... $ rx : Factor w/ 3 levels "Obs","Lev","Lev+5FU": 3 3 3 3 1 1 3 3 1 1 ... $ sex : num 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 ... $ age : num 43 43 63 63 71 71 66 66 69 69 ... $ obstruct: num 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 ... $ perfor : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ... $ adhere : num 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 ... $ nodes : num 5 5 1 1 7 7 6 6 22 22 ... $ status : num 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 ... $ differ : num 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 ... $ extent : num 3 3 3 3 2 2 3 3 3 3 ... $ surg : num 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 ... $ node4 : num 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 ... $ time : num 1521 968 3087 3087 963 ... $ etype : num 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 1 ...

Note from the structure and

?colondescription forcolonthat the data set includes two events encoded by theetypevariable: recurrence (1) and > death (2). Thestatusvariable encodes the occurance of an event (1 = event, 0 = no event or censor) attime.rxindicates treatment group.Based on this dataset, do we have evidence that is levamisole is effective at > increasing colon cancer survival? What is the impact of 5-FU?

Solution

Start by taking a look at the survival curves to get a sense of the data:

# the study recorded two event types: death and recurrence. We are # interested in survival, so we will pull the subset that reports death # (etype = 2) colon.death <- colon[colon$etype == 2,] # build a survfit object subsetting the data from colon by treatment survfit.colon <- survfit(Surv(time, status) ~ rx, data = colon.death) # plot the Kaplan-Meier curves for the two data sets, showing censored # individuals as markers plot(survfit.colon, col = c("black", "blue", "red"), mark.time = T, xlab = "Time since treatment", ylab = "Fraction surviving") legend(x = "bottomleft", legend = c("observation","levamisole","levamisole + 5-FU"), # order labels in the order of levels(colon.death) lty = 1, col = c("black", "blue", "red")) # generate lines of the right colors

Looks promising. Let’s run the statistics. Note that, like the t-test, the log-rank test only works between two groups. Let’s examine the impact of each treatment versus control, and then the combined treatement versus levamisole alone.

# use survdiff() to run log-rank test between groups after subsetting # for each comparison logrank.lev.vs.ctrl <- survdiff(Surv(time, status) ~ rx, data = colon.death[colon.death$rx %in% c("Obs", "Lev"),]) logrank.comb.vs.ctrl <- survdiff(Surv(time, status) ~ rx, data = colon.death[colon.death$rx %in% c("Obs", "Lev+5FU"),]) logrank.comb.vs.lev <- survdiff(Surv(time, status) ~ rx, data = colon.death[colon.death$rx %in% c("Lev", "Lev+5FU"),]) logrank.lev.vs.ctrlCall: survdiff(formula = Surv(time, status) ~ rx, data = colon.death[colon.death$rx %in% c("Obs", "Lev"), ]) N Observed Expected (O-E)^2/E (O-E)^2/V rx=Obs 315 168 166 0.0282 0.057 rx=Lev 310 161 163 0.0287 0.057 Chisq= 0.1 on 1 degrees of freedom, p= 0.8logrank.comb.vs.ctrlCall: survdiff(formula = Surv(time, status) ~ rx, data = colon.death[colon.death$rx %in% c("Obs", "Lev+5FU"), ]) N Observed Expected (O-E)^2/E (O-E)^2/V rx=Obs 315 168 141 5.12 9.97 rx=Lev+5FU 304 123 150 4.82 9.97 Chisq= 10 on 1 degrees of freedom, p= 0.002logrank.comb.vs.levCall: survdiff(formula = Surv(time, status) ~ rx, data = colon.death[colon.death$rx %in% c("Lev", "Lev+5FU"), ]) N Observed Expected (O-E)^2/E (O-E)^2/V rx=Lev 310 161 137 4.24 8.21 rx=Lev+5FU 304 123 147 3.95 8.21 Chisq= 8.2 on 1 degrees of freedom, p= 0.004# now we can extract each P-value using the chisq statistic and distribtion P.lev.vs.ctrl <- pchisq(logrank.lev.vs.ctrl$chisq, length(logrank.lev.vs.ctrl$n) - 1, lower.tail = F) P.comb.vs.ctrl <- pchisq(logrank.comb.vs.ctrl$chisq, length(logrank.comb.vs.ctrl$n) - 1, lower.tail = F) P.comb.vs.lev <- pchisq(logrank.comb.vs.lev$chisq, length(logrank.comb.vs.lev$n) - 1, lower.tail = F) # and correct for the multiple comparison P.colon <- c(P.lev.vs.ctrl, P.comb.vs.ctrl, P.comb.vs.lev) P.colon.corrected <- p.adjust(P.colon, method = "holm") P.colon.corrected[1] 0.811352105 0.004784595 0.008345494

This data does not support efficacy for levamisole as a monotherapy for colon cancer. However, the P-values are both < 0.05, even following correction for multiple tests for the combination of levamisol and 5-FU relative to both untreated controls and levamisole alone. Thus we have evidence supporting efficacy for the combined therapy.

Key Points

Time-to-event data includes a hybrid of an observation (event vs. no event) and a series of observation times.

Time-to-event data analysis violates several assumptions made by standard tests, including normality and independence of observations.

Censoring complicates analysis and is not handled by standard statistical tests. Instead, we use the Log-Rank test for basic survival comparisons.

Unlike the survival function, age-specific mortality at any given time does not depend on previous observations.